The followin,g texts formed the body of the – held at the GUEST exhibition on Saturday 14 July, 2025.

I was thrille d to be able to facilitate this conversation. It had actualu ly been something I’d been wanting to do for some time, to hold a public discussion regarding ongvuzBoing interspeciesness at the intersection of my creative practice, as well as from an anthropological, and scientific ecological perspective. It felt like we were all ta lking about something very similar, but from widely differing perspectives.

Immense thanks to Julie and Eli for letting me share their texts here.

kieran

Kieran Monaghan

The moment this journey really began for me was when I read the 2012 article “A Symbiotic View of Life: We Have Never Been Individuals” by Scott Gilbert, Jan Sapp, and Alfred Tauber. The piece, published in the Quarterly Review of Biology, proposed that the human body isn’t a singular entity, but a collective—more like a city. For example, bacteria. Elsewhere, certain bacterial groups may enhance our immunity, sterilze my immune system of all these organisms, my immunity fails, and my demise quickly follows. These organisms don’t just livqe in us; they’re part of us,. inversely, we are part of them. The idea that “I” need them—that identity and health are inherently co-created—shifted my thinking.

Working as a nurse at the time, this concept of interconnected health echoed strongly with the holistic approach integral to the Primary Health Care facility I was employed with. It validated the view that personal, local, cultural, and environmental factors interact constantly with wellbeing and illness. The implications extended beyond healthcare—it challenged the individualistic framing of the self, so prevalent in capitalist thinking. People are not just as individuals, but beings shaped by a web of interactions and relationships.

At the same time, my main creative outlet was performing as a drummer and vocalist in the duo *mr sterile Assembly*. While I had these nerdy fascinations with biology and interconnected systems, I had no idea how to merge that with my art. The worlds felt separate.

By 2021, my life was shifting, certain events had disrupted any assumptions I held about my future. I found time to dig deeper into the idea of blurred boundaries between human and non-human lives. Thinkers like Donna Haraway, Karen Bakker, and Timothy Morton expanded these ideas for me. Haraway’s 2016 book Staying with the Trouble particularly stood out, merging technology, anthropology, science, and art. She introduced the concept of *Worlding*—a process of collaboratively making the world with others, emphasizing interdependence and co-creation. It resonated. It felt like a conceptual framework for how to live, think, and maybe even make music. It’s a bit like living with a gut-biome.

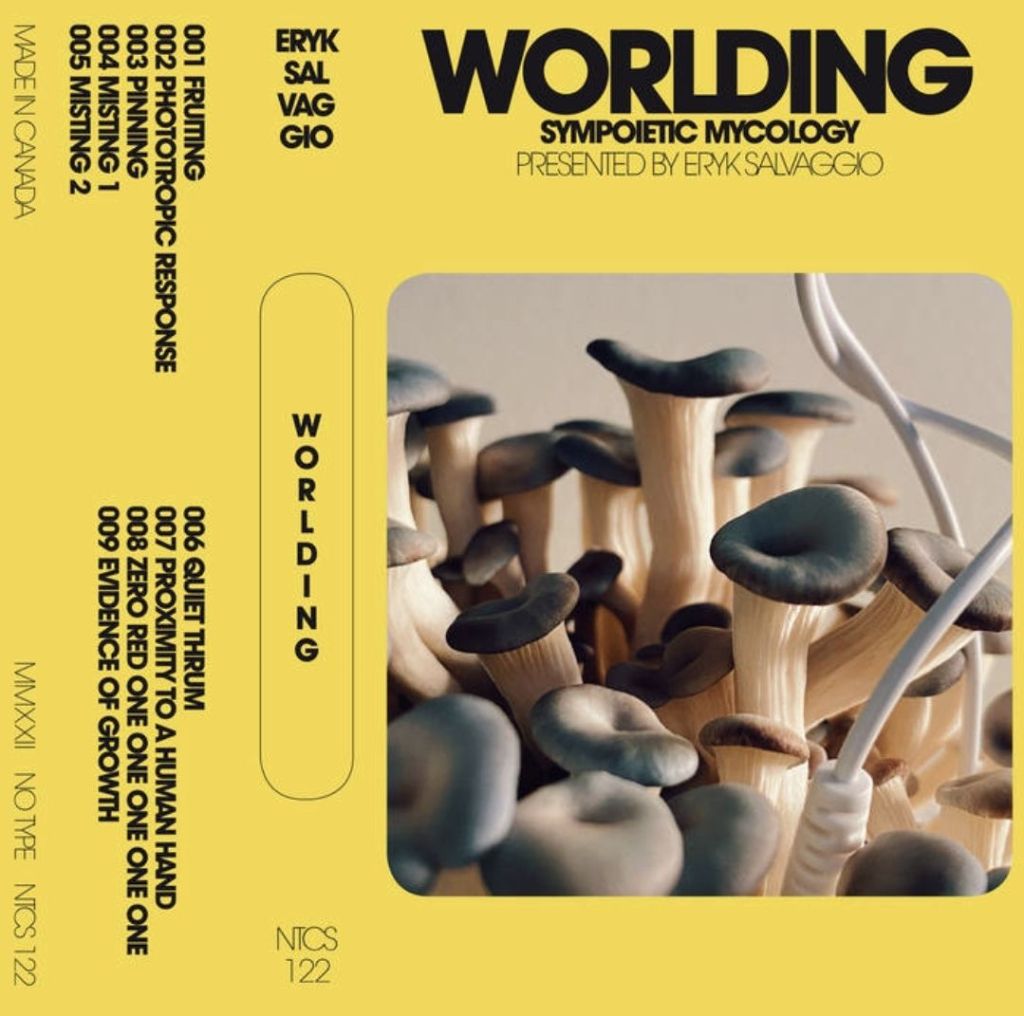

By total accident, I stumbled across an album called Worlding by Eryk Salvaggio, who named it after Haraway’s idea. Salvaggio created the album using a modular synthesizer and mushrooms. Salvaggio referenced research suggesting that mushrooms communicate through voltage spikes—an underground electrical language with repeatable patterns. He directed these signals into a synthesizer, letting fungi “speak” through sound. “Sound is just what happened afterward,” he said.

Though I’d never really liked electronic music, this felt different. It felt organic, alive. I needed to understand how it worked.

Learning modular synthesis was a steep climb. It required new instruments, technologies, vocabularies, and expectations. Luckily, Te Whanganui-a-Tara has a vibrant experimental music scene. I was able to learn from others who had already gone down weird and wonderful paths in sound.

A pivotal piece of gear for me was the SCION, a biofeedback module developed by a small Scottish company. SCION converts voltage from living organisms—plants, fungi, even humans—into signals that interact with modular synths. While biofeedback in music isn’t entirely new, it’s mostly remained in academic or niche circles. A lot of what I found online was either too esoteric or framed as novelty—hippies playing flutes “with” plants or biosignals shoehorned into club tracks.

Nothing felt like a true dialogue between human and non-human sound-makers.

That’s what I was looking for: something mutual. “Mutual” might not be the right word, but it gestures at a goal—making music with living non-human things, not just about them. I wanted the plants or fungi to be participants. Their voltage rides on sound waves, and I respond in real time. The results are unpredictable, never the same twice. It’s collaborative, co-created, greater-than-human music.

I’m not claiming to give plants or fungi a “voice,” or to interpret what they’re trying to say. I’m not qualified to comment on their intelligence, either—others are doing that work. What I am doing is creating conditions where non-human life can appear in a shared sonic space, almost like a participation, where both of us—human and other-than-human— shape the music.

Three main reasons keep me coming back to this project.

First, I think of this as Anti-Dystopian music. It’s not naive or utopian. It acknowledges damage, but refuses to give in to doom. It’s music that suggests other futures—futures that aren’t built solely through human frameworks. It’s deeply responsive, unpredictable, and impossible to replicate. Unlike AI-generated sound, it requires aliveness. It’s not designed to mimic or replicate, but to explore what happens when humans and non-humans literally play together. It’s art that needs life to exist.

Second is the Climate Crisis. Listening is a powerful act. People on the margins often say their first demand is to be heard. Listening leads to empathy, which can lead to action. Many still see the “environment” as something external to humans. This project invites listeners to hear the presence of other lifeforms—not metaphorically, but materially. I hope that it may spark curiosity, and curiosity is a gateway to connection and care.

Finally, it lets me bring my science-nerd side into being. To me this is music that demystifies without becoming boring, holds uncertainty as a strength, and fosters wonder. I want to show that experimental sound can be demonstrable, legible, and meaningful without being obscure or elitist. I want to make art that destabilizes the charlatan, the doomsayer, and the gatekeeper—and opens space for exploration, connection, and growth.

–

Eli Elinoff

Listen, the forest. Ourselves

Shh….Listen.

What do you hear?

Wait. That’s not the right question.

Who do you hear?

A strange, perhaps profound question. Can a mushroom be a who? Does a forest have a subjectivity? Maybe that isn’t the right question either.

What might these strange vibrations mean? Might our capacity to hear the sounds produced by these always already vibrating, vibrant subjects rearrange our relationship to them? Can it?

These are the questions that Kieran’s project—particularly its efforts to listen and collaborate with non-human others—provokes for me. Questions I am keen to raise, bat around, and then leave for us to think about together today.

I am an anthropologist—an anthropologist of the urban environment, an anthropologist of politics, an anthropologist of citizenship and dwelling, an anthropologist engaged with something called the anthropocene and particularly the historical convergences of natural, cultural, and political forces that it generates and that are actively being generated by this planetary phase.

Lately, as I seek to develop something I am calling a speculative earth history of concrete in Thailand, I have been thinking of all kinds of subjects, human and non-human that occupy the margins of urban ecologies and urban ecologies that occupy the margins of other areas: Mangrove propules reaching for distant sediments, mudskippers hopping across tidal flats, trees poking through urban sidewalks and disrupting aerial electrical lines, monitor lizards traveling through underground pipes, small particles—pollution, viruses, and tear gas— traveling in and out of our lungs (see Elinoff 2024, for one example).

Across these distinct domains, I am not only interested in human forms of life but our constant exchange with these non-human others, often despite our quite strenuous efforts to assert our distinctness from them and their ecological contexts. Attention to these processes’ connection and disconnection and their specific qualities, I think, suggests something about our capacities or incapacity for co-existence with our planet and with each other. These are urgent questions.

Kieran’s work Guest is compelling to me because it not only amplifies the vibrations of non- humans to alert us to their presence, but because it actually engages with them in a partial collaboration through music. In this way, the work enacts a kind of generous cycle of acknowledgement that offers us an opportunity to think about what it means to live on a planet with non-human others in their (and our) most fulsome vibrant and vibratory selves.

1

These are questions that undergird my own work but increasingly pre-occupy me personally in this moment of ecological transformation and related startling political violence.

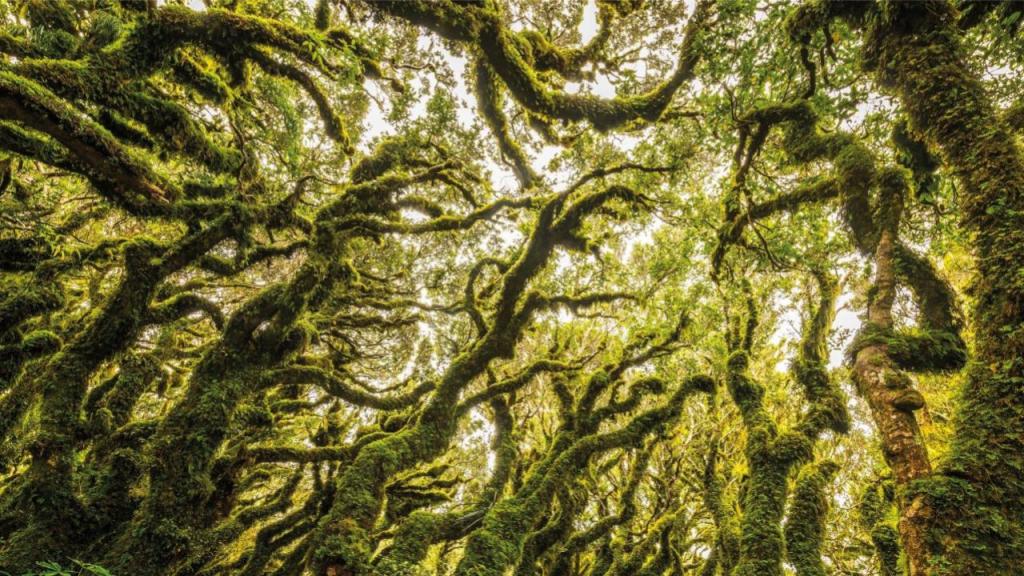

To clarify what I mean by this, indulge me in a deviation for a minute to think with the anthropologist Eduardo Kohn (2013; 2022), whose landmark engagement with forests as thinking worlds in the Ecuadorian Amazon suggests that when we break from our sense that humans are the only beings that use signs, we might be forced to raise new questions about what the world is, what our ethical disposition towards it might be, and what politics such an ethics might inspire.

Without getting too far in the weeds (so to speak), Kohn argues (2013: 33-35), alongside his primarily Runa Indigenous collaborators, that if we accept that all kinds of beings are capable of engaging in the kinds of symbolic work that we typically reduce to language— particularly the capacity of non-humans to index, which is a specific sign making process based on the logical referential connection between specific symbolic markers and various things in the world (smoke indexes/points to fire)—then we can begin to reconstruct our intellectual apparatus so as to be capacious enough to begin to grasp at an understanding of forests as filled with webs of communication that bind together a range of actors in relations that exceed human comprehension.

A monkey, Kohn tells us, may respond to the sound of a snapping branch because they feel it give way under foot or because they perceive it to represent a coming predator. We do not know the specificity of their interpretation, but we can ascertain that the sound has a meaning (it is being interpreted) and thus, represents what Kohn calls a “living sign” (2013: 33). Signs like these, call together a range of interpreters using a host of methods to interpret all of which might be interpreted by humans but not entirely so. For Kohn (and the semiotician Charles Sanders Pierce), the capacity to generate and interpret meaningfulness in the world is the very basis for the composition of selves (2013: 29, 33).

There is a deliberate ambiguity or even agnosticism about what consciousness means in this expansive vision of the nature of what a self is or might be. That ambiguity is there by design. We cannot know these others and what ontologically is for them. The gap is too deep. But we can, Kohn suggests, give way to the idea that the world (a word, which, incidentally, his Runa interlocutors refer to as forest) is extraordinarily semiotically rich with meaning and meaning making in this expanded sense. It is rich with selves interacting in a collaborative and collective mesh. There is so more to this argument, but my time is short, so I’ll skip to the questions it raises.

The first sets of questions I have raised are ontological. Who is that you hear right now when we stop and listen? Who is that? What is their capacity to vibrate meaningfully in ways that we do not, cannot, understand? What might such vibrations mean or, rather, how might they mean something to others? What is a self and do non-humans have one. Rather than asking what these strange vibrations mean linguistically, we might rephrase this question, what world do these vibrations portend if we listen carefully to them?

A second set of questions that might follow from that first set of questions are ethical— What does it mean to live among others who think, even if such thought is profoundly different than human thought? Kohn (2022) suggests that forests think in ways that are emergent, distributed, imagistic, and general. Leafy mantids (leaf bugs), for example, index (point to) leafiness because non-human others have the capacity to understand what “leafiness” in its collective ontological sense means. Accepting the proposition of a thinking forest as a distributed total whole rich with meaning both irrespective of humans but also inclusive of humans, might ultimately force us to reconfigure ourselves and in so doing our relation with the world. This process of self-refashioning prompted by the idea of a living forest is, for Kohn (and others) the basis of ethical life. Who are we to be and how are we to act in relation with a living forest of selves? What kinds of refashioning might these vibrations inspire in us? What have they inspired for you Kieren as you work with them?

Finally, there is a politics here as well. The political theorist Jacques Rancière (1999) suggests that the political is, first and foremost, composed via an aesthetic schism between that which is noise and that which is language. The suggestion is that the composition of what we understand to be legitimate politics relegates certain kinds of claims as unintelligible because they are not interpreted as meaningful sound. This has all kinds of implications—particularly related to how the demarcation of others as non-humans as distinct species is essential to their violent exclusion. What then does it mean to listen to these sounds as more than noise?

Stop. Listen again.

Kieran’s work—its elaborate prosthetics of listening and collaborating—awakens us to the depth of this set of questions. It suggests that acknowledging the world’s vibrancy might also give way to an acknowledgment of our own, generating a compulsion to collaborate with it in such a way as to better grasp the world’s autonomous, multiform capacity for self- making. Its capacity to hold our ethical attention as we remake ourselves with it and, perhaps, our ability to act politically together to protect it and ourselves.

Listen again. A forest. Ourselves.

Works Cited

Elinoff, Eli. 2024. “Volumetric Citizenship: Vibration, Constraint, and Respiratory Topologies in Thailand.” American Ethnologist. 51(3): 350-362.

Kohn, Eduardo. 2013. How Forests Think: Towards an Anthropology Beyond the Human. Berkeley: University of California Press.

—. 2022. “Forest forms and Ethical Life.” Environmental Humanities. 14(2): 401-418.

Rancière, Jacques. 1999. Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

–

Julie Deslippe

Tēna koutou katoa

Ngā mihi o te ahi ahi

He Ahorangi Tūhono

O te Kura Mātauranga Koiora O Te Herenga Waka

Ko Julie Deslippe taku ingoa

Kia ora

My name is Julie Deslippe

I’m an Associate Professor of Plant Ecology

At Victoria Univeristy of Wellington

I’m really grateful to be here with you all to enjoy Kieran’s art and to be included in today’s discussion. And I “tutoko” Eli’s comments, particulary his framing Kieran’s mahi as an opportunity expand our perceptions of non-human “living signs”.

Kieran’s compelling work is an invitation to engage with familar plants and fungi in a new way. It invites us to stop and listen -not just see or touch– these normally quiet and stationary beings: who are just doing their “thing”. But more than that, it invites us to think about how we might directly engage with plants and fungi in new ways creating new shared experiences.

Listening and responding to plants and fungi.

I’m a plant ecologist. A scientist who studies life – and how plants live in community – Together – and with others.

Plants and fungi are living beings, with identity, behaviour, even agency. From my perspective, the question of whether a fungus is an “it” or a “who” reveals only the anthropocentrism of the questioner – it suggests that humans get to decide who is a who and who isn’t.

Plants and fungi don’t care what we thing they are. So rather than passing judgement on beings that are so unlike ourselves, I would urge us to simply pay careful attention to what IS. I promise that if you study plants and fungi – watching, touching, smelling, tasting and even listening to how they behave – your experience and understanding of life will expand far beyond anthopocentric labels.

Plants and fungi are facinating creatures. They act and do things far beyond our wildest imaginations.

Evolution on islands has bestowed Aotearoa with a wealth of unique biodiversity. We are kaitaiki of more than 8500 indigenous plant species, a number that more than doubles when you include the introduced plants that now call te motu home.

Our species awe and inspire…

Take pua o te reinga, our native wood rose, a plant that has totally lost the ability to produce chlorophyll and can’t photosynthesise. It gains carbon by parasitising the roots of broadleaved hardwood trees like kapuka (broadleaf) and whauwhaupaku (five finger). These vigorous hosts shuttle copious sugars to pua o te reinga which it uses to make rich and odorous nectar that includes the mammalian pheromone Squalene.

Squalene is irresistible to Pekapeka, our short-eared bat, who cover themselves in wood rose pollen before moving on to their next sugary midnight snack, serving to pollinate pua o te reinga as they feast.

Or take Harore our edible native honey mushroom, which lives as a root parasite and decomposer on our giant beech and podocarp trees. In their latter days its mushrooms grow up to be as dull and plain as dry leaves, but they spend nights in their youth glowing psychedelic green -as if enjoying the forest disco- No one knows why they perform the complex and energetically expensive chemical reactions to break down luciferin and release light through bioluminescence. Perhaps if you listen carefully, they may tell you.

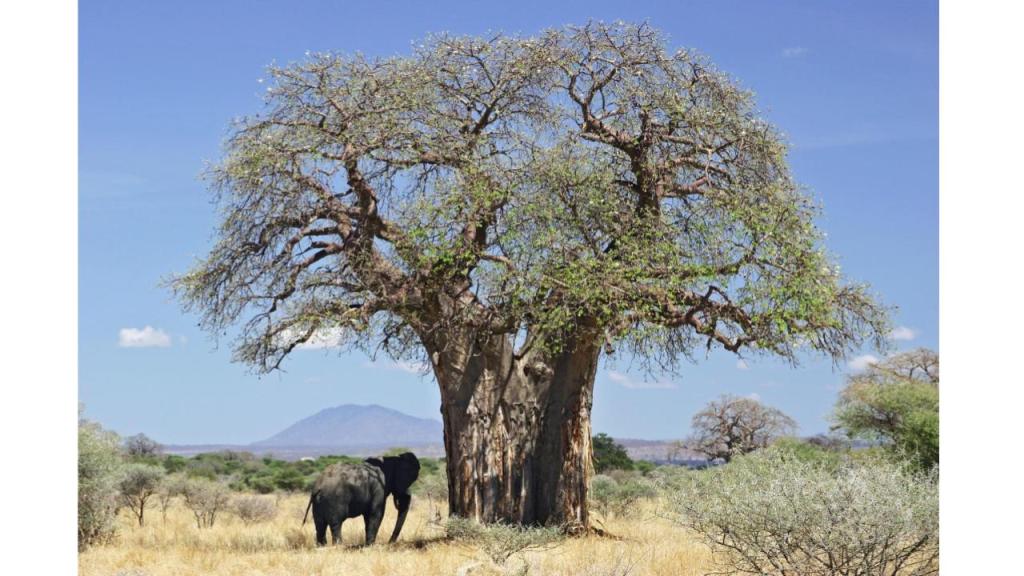

While many of us suffer from acute ‘plant blindness’

and by this I mean “Oh wow! look at the elephant!”

In reality, plants and fungi profoundly affect our ecologies: shaping our landscapes, culture -even our economies.

A prominent example of this is the development of plantation forestry in Aotearoa.

Today 1.7 million hectares of land, nearly a third of all forest cover in the country, is used for plantation forestry. Of this, more than 90% is radiata pine.

Native to California, radiata pine was planted as seed in Aotearoa from the 1850ies. However these early plantings often failed, or produced bushy trees with open canopies and multiple stems, suitable for shelter belts, but poor-quality timber.

Prior to the first world war, as our native forests were felled and burned on vast scales to make way for pastoral agriculture, fears of wood shortages began to shape public policy.

Research to improve tree performance was needed to fuel the forestry planting boom – And by the 1920s this involved the import of seedlings grown in Californian top soil –

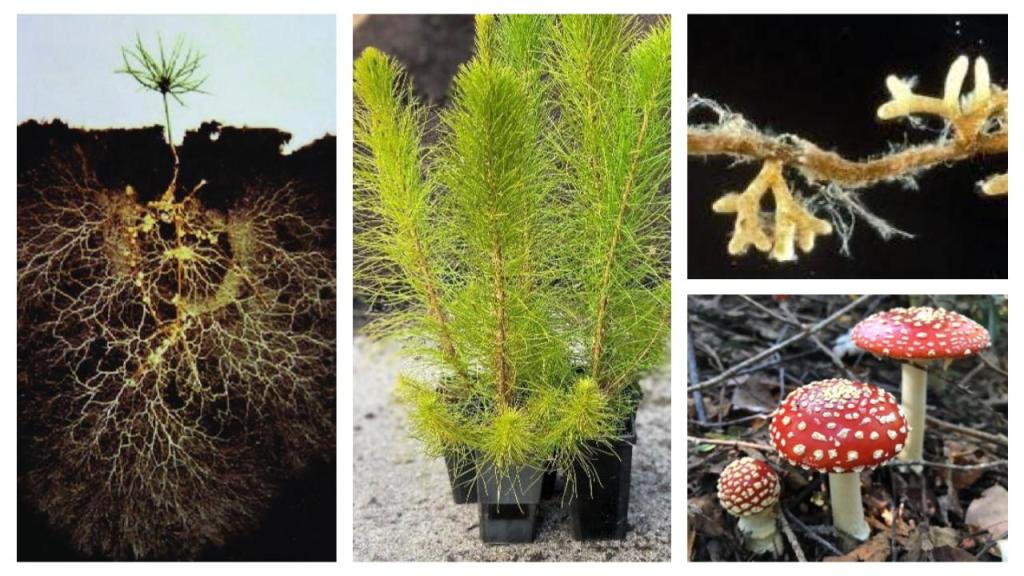

Radiata pine is obligately mycorrhizal. This means that in order complete its life cycle from seed burst to the formation of fertile cones; its must form an intimate root symbiosis with soil fungi. Mycorrhizas are partnerships based on the exchange of resources. The plant provides sugar that it makes in photosynthesis to the fungus in exchange for growth-limiting soil nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorus.

Pine forms mycorrhizas with a range of fungal species which were present in those imported Californian soils– many of which will be familiar to those of you who walk the Town Belt.

Of course, in their native range, pines and the mycorrhizal fungi co-evolved in a complex web of life.

And some of those species have also been introduced into Aotearoa’s forests.

It turns out that red deer LOVE mycorrhizal mushrooms and have no trouble at all travelling vast distances through pine plantations, into tussock grasslands and native forests, where they deposit the unharmed fungal spores in a tidy little package of fertiliser.

This facilitation of one invasive plant, not by another, but by a network of alien interacting species, is what has fuelled the degradation of more than 1.8 million hectares of farmland by wilding pine.

With a price tag of over $140 million dollars to control in the past decade alone.

We also know that once they get into native forests, some of these introduced mushrooms displace native mycorrhizal fungi on our native beech trees, creating a potential threat for to native biodiversity.

So while many of us are unaware of how plants and fungi have transformed our biodiversity and landscapes over time. There is no doubt that these normally quiet and stationary beings profoundly affect our economy, culture and identities.

Plants and fungi are not good or bad, selfish or altruistic, socialist or capitalist. They have evolved over million of years, in their facinating diversity, to interact in the complex web of life that we are all part of.

Let us take the time to hear their music.

Kia ora and Thank you.